Commercial work trucks, box trucks, service units, utility rigs, contractor vehicles, tow trucks, telecom trucks, municipal fleets, are the backbone of local and regional business in the United States. They deliver packages, fix power lines, haul tools, tow disabled vehicles, and keep cities running. They are everywhere, all day, every day.

As these trucks age, especially once they pass the 100,000 to 150,000 mile mark, a very consistent pattern shows up in fleet maintenance data. Electrical failures start to outnumber almost everything else. It is not always engines. It is not always transmissions. It is electrical issues that send these trucks to the shop again and again.

Ask a fleet manager what puts their work trucks in the bay most often and you will hear the same answers. Electrical issues. Wiring problems. Sensor failures. Alternator faults. Battery drain. Module communication errors. In other words, not the big iron, but the invisible nervous system that keeps everything powered and talking.

The reason is simple but often overlooked. Class 3 to 7 commercial trucks live a completely different life than a highway semi. Their electrical load is heavier, more chaotic, and more abusive. Their duty cycles are full of idle time, stop and go driving, short trips, and constant cycling of PTOs, lifts, booms, pumps, and tools. That combination destroys electrical systems faster, creates intermittent faults that are hard to diagnose, and drives up downtime and cost.

This guide explains why work trucks have higher electrical failure rates, what typically fails, what those repairs cost, and how fleets can reduce the damage. It also shows where warranty coverage, including TruckProtect, fits naturally into a realistic fleet strategy, without hype, just practical risk management.

Commercial Trucks Are Not Miniature Semi Trucks, Their Electrical Load Is Completely Different

On paper, a Class 7 box truck and a Class 8 tractor might look similar. Both have diesel engines, alternators, batteries, and wiring harnesses. But the way they are used could not be more different.

A typical semi is designed for long, steady highway runs. It spends hours at a time at consistent RPM, with stable voltage, predictable alternator output, and relatively clean electrical loads. Yes, there are hotel loads, inverters, and some auxiliary systems, but the pattern is smooth.

Commercial work trucks are designed for work, not for long haul cruising. A single truck might run a PTO driven crane in the morning, power a hydraulic lift in the afternoon, and sit idling with HVAC and tools running in the evening. It might be wired for pumps, winches, booms, inverters, auxiliary lighting, refrigeration units, telematics, GPS, cameras, safety sensors, and mobile work equipment, all pulling power from the same electrical backbone.

Layer on top of that the way these trucks move. Stop and go urban driving. Delivery cycles with dozens or hundreds of starts and stops per day. Heavy idle time on job sites. Short trips that never let the batteries fully recharge. Variable voltage draw as equipment cycles on and off. Constant key cycles that hammer starters and alternators.

The result is simple. The electrical system in a work truck lives a harder life than the electrical system in a highway tractor. It is asked to do more, in harsher conditions, with more add ons, and less stable operating patterns. That is why failure rates are higher, especially as these trucks age.

Top Reasons Commercial Work Trucks Experience More Electrical Failures

Extreme Idle Time Creates Battery Strain

Commercial trucks idle more than almost any other vehicle type. Delivery routes, service calls, roadside repair, HVAC vans parked outside a job, bucket trucks holding a worker in the air, municipal units running lights and tools while stationary, all of these rack up idle hours.

When a truck idles, alternator output is often lower and less consistent. Batteries slowly discharge while supporting lights, HVAC, tools, and electronics. Components sit in high under hood heat without the cooling airflow of highway speed. The result is premature battery wear, failing alternators, tired starters, random module resets, and increased sensor failures.

Semi trucks idle too, but work trucks tend to idle more often and in more abusive patterns. Short idle, shutdown, restart, idle again. That constant cycling is hard on every electrical component in the system.

Stop and Go Driving Creates Voltage Instability

Every time a truck restarts, the starter draws a huge surge of amperage. The alternator then has to catch up and recharge the batteries. Voltage spikes and dips are normal in that process, but when you multiply it by the number of stops a work truck makes in a day, the stress becomes extreme.

A parcel delivery truck might stop 80 to 150 times per day. A service truck might restart at every job. A tow truck might cycle the engine with every hook and drop. Municipal trucks can restart dozens of times in a single neighborhood. Each event is a heavy electrical shock to starters, alternators, modules, and wiring.

Over time, this constant stop and go pattern accelerates wear. Modules see more power cycles. Solder joints and connectors see more thermal and electrical stress. Batteries rarely get a long, healthy charge cycle. Voltage stability suffers, and sensitive electronics pay the price.

PTO Operation Loads the Electrical System Heavily

Many commercial trucks rely on PTO systems to power hydraulic pumps, booms, cranes, winches, lifts, and other work equipment. When a PTO is engaged, the engine may run at a set RPM, but the electrical system is under unusual load.

PTO usage increases alternator load, spikes electrical demand, creates heat in wiring and connectors, stresses batteries, and interrupts stable voltage flow. The system is trying to run the truck, charge the batteries, and feed power hungry work equipment all at once.

Most electrical systems were not originally designed to handle that kind of continuous, variable load while also dealing with frequent starts, stops, and idle time. Over years of service, this combination accelerates alternator wear, wiring fatigue, sensor failure, and module stress.

Harsh Operating Environments Punish Wiring and Modules

Unlike semis that spend most of their lives on highways, commercial trucks live in neighborhoods, job sites, construction zones, muddy access roads, icy streets, and rain soaked locations. They park under trees, back into alleys, sit near welders and grinders, and work around chemicals and debris.

They are exposed to water, dust, mud, salt, metal shavings, and harsh cleaners. All of these attack wiring harnesses, connectors, seals, and modules. Moisture intrusion alone is one of the top causes of intermittent electrical issues in work trucks. A little water in a connector today can become a corroded, high resistance, intermittent failure a year from now.

Massive Amounts of Auxiliary Equipment Create Overload and Complexity

Most commercial trucks do not stay stock for long. Fleets add ladder racks with lighting, inverter systems, tool power circuits, GPS and telematics, dash and body cameras, refrigeration units, dual battery setups, extra switches and relays, and a variety of aftermarket installs.

Every additional device adds new failure points, new voltage loads, more wiring complexity, and more heat. Many of these installs are not done to OEM standards. They might be functional, but not truly fleet grade. Over time, poor crimps, unsealed connectors, undersized wire, and improvised grounds become chronic failure sources.

Vibration and Job Site Abuse Damage Electrical Systems

Work trucks endure constant frame flex, vibration, uneven loads, potholes, rough terrain, and off road impacts. They drive over curbs, into yards, onto gravel, and through construction zones. This physical punishment loosens grounds, shakes connectors, stresses wiring junctions, and compromises module seals.

Semi trucks experience vibration too, but usually on smoother surfaces and with more predictable loads. The daily abuse a bucket truck or service body sees on a rough job site is in a different league.

Heat Cycles Destroy Electrical Components Over Time

Urban and vocational duty cycles create extreme heat cycling. A truck idles in traffic or on site, under hood temperatures climb. Then it shuts down and cools. Then it restarts, heats up again, runs a short trip, and idles once more.

Every cycle contributes to wire insulation cracking, module fatigue, sensor resistance changes, and solder joint failure. Over three to seven years, heat becomes one of the primary drivers of electrical degradation, especially in engine compartments and under dash areas with poor airflow.

Short Routes Limit Alternator Charging Time

Commercial trucks often make dozens or even hundreds of short trips per day. The engine might run for a few minutes, shut off, then restart again. In that pattern, batteries rarely reach a full, healthy charge. Alternators are constantly playing catch up. Starters are abused. Voltage remains unstable.

A delivery van running 150 stops daily can easily see three to four times the electrical wear of a semi that runs a few long legs per day. The alternator and battery system never get a break.

Moisture Intrusion and Corrosion Drive Early Failures

Moisture finds its way into headlight assemblies, taillights, connectors, hood seams, underbody wiring, door seals, and even fuse boxes. Once there, it starts the slow process of corrosion.

Corrosion and moisture cause shorts, blown fuses, dead circuits, module communication errors, lighting failures, and CAN bus instability. Left unchecked, corrosion can slowly take out an entire wiring system, one connector at a time.

Older Work Trucks Rarely Get Dealer Level Electrical Care

Most commercial fleets rely on in house mechanics, quick service centers, and mobile repair vendors. These teams are excellent at oil, brakes, tires, belts, and fluids. Electrical diagnostics, however, are more complex, more time consuming, and often require specialized equipment and software.

As a result, electrical issues are more likely to be misdiagnosed, temporarily patched, or deferred. Intermittent faults may be cleared without being fully solved. Over time, this leads to repeat failures, stacked problems, and larger, more expensive breakdowns that could have been prevented with deeper diagnostics.

The Most Common Electrical Failures in Commercial Work Trucks

Across Class 3 to 7 fleets, certain electrical failures show up again and again.

Alternator failures are near the top of the list. Heat, idle time, PTO load, and constant cycling destroy alternators faster in work trucks than in highway tractors. Replacements typically run 400 to 1,200 dollars, not counting diagnostics.

Starter motor failures are also common. Short cycle routes overheat starters and wear brushes and solenoids prematurely. Starters usually cost 300 to 1,000 dollars to replace.

Batteries fail more often because they are constantly being discharged and recharged in short bursts. A commercial duty battery might cost 150 to 400 dollars, but when you run dual or triple setups across a fleet, the numbers add up quickly.

Sensors, including NOx, temperature, pressure, and speed sensors, fail at higher rates in commercial trucks because they live in more contaminated environments and see more heat and vibration. Each sensor can run 250 to 900 dollars, and some require significant labor to access.

CAN bus communication failures are another headache. Loose connectors, moisture, and corrosion can cause network errors that are time consuming to trace. The parts might be cheap, but diagnostics can run into the hundreds or thousands of dollars.

Wiring harness damage is often the most expensive electrical issue a fleet faces. A major harness replacement can easily cost 800 to 5,000 dollars or more, especially if the harness runs through the cab or frame.

Module failures, ECM, TCM, BCM, body control modules, are common once trucks have seen years of heat cycling and voltage instability. These components typically cost 1,200 to 3,500 dollars or more and often require programming.

PTO related electrical faults are highly variable, but they are frequent. Hydraulic pump systems, boom controls, and lift circuits all stress alternators, wiring, and modules. Repairs can range from a few hundred dollars to several thousand, depending on how deep the damage goes.

Why Electrical Failures Become Expensive Even When Parts Are Cheap

One of the most frustrating things about electrical issues is that the part itself is often not the real cost driver. A sensor might cost 65 dollars. A connector might cost 20. A fuse is a few dollars. But finding the root cause can take hours.

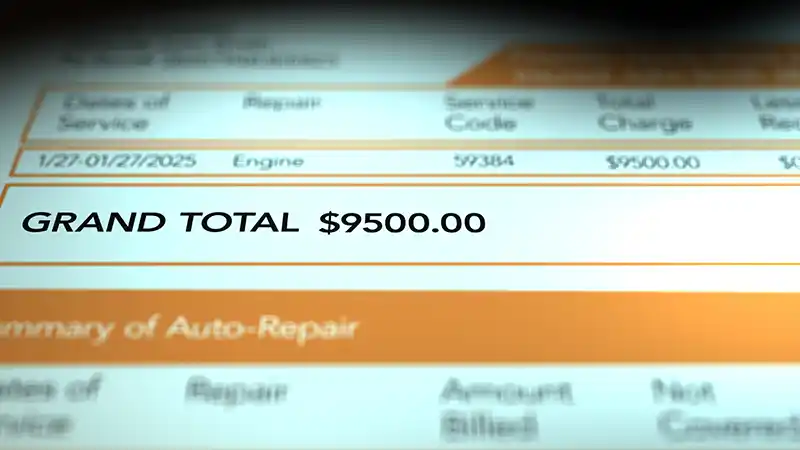

Electrical diagnostics often require long diagnosis time, tracing intermittent faults, using advanced scan tools, performing module programming, resetting CAN bus networks, and inspecting wiring harnesses end to end. It is common for a 150 dollar part to require 2 to 4 hours of labor and 200 dollars of dealer level diagnostics, turning a simple failure into a 1,000 dollar invoice.

For fleets, the real cost is a combination of parts, labor, diagnostics, and downtime. A truck that is down for electrical work is not generating revenue, and the driver may be idle as well. That is why electrical failures feel so painful, even when the hardware itself is not as expensive as an engine or transmission.

Total Electrical Failure Costs For A Typical Fleet

When you zoom out to the fleet level, electrical failures become a major budget line item.

A very small fleet with 1 to 3 trucks might see 1,200 to 6,000 dollars per year in electrical failure costs. A 4 to 10 truck operation may spend 4,000 to 20,000 dollars annually. Fleets in the 10 to 30 truck range can easily see 12,000 to 60,000 dollars per year. Larger fleets with 30 or more trucks may face 36,000 to 200,000 dollars or more in annual electrical related spend.

These numbers include alternators, starters, sensors, modules, harness repairs, diagnostics, and idle related wear. They do not always show up as a single big invoice. Instead, they drip out across the year as a steady stream of smaller but frequent repairs.

How To Reduce Electrical Failures In Commercial Work Trucks

Fleets cannot eliminate electrical failures, but they can reduce their frequency and severity.

Reducing idle time where possible helps cut heat and strain on alternators and batteries. Cleaning and protecting electrical connectors, especially in high exposure areas, keeps moisture and corrosion at bay. Avoiding unnecessary aftermarket electronics, or at least insisting on fleet grade installs, reduces overload and complexity.

Regular inspections of alternators and starters for heat stress, corrosion, and noise can catch problems early. Investing in high quality batteries, rather than the cheapest option, pays off under heavy commercial demand. Keeping grounds clean and tight is critical, as loose or corroded grounds are behind many nightmare diagnostic stories.

For trucks with PTOs, booms, or heavy auxiliary loads, upgrading to fleet grade wiring, properly sized alternators, and robust power distribution can dramatically improve reliability over the life of the vehicle.

Where Warranty Coverage Helps

Electrical failures are unpredictable, and they are expensive mostly because of labor and diagnostics. You rarely know which truck will throw a code next week or which harness will finally corrode through.

Because of that, programs like TruckProtect that include electrical components can offer real world financial relief, especially for older commercial trucks that are past OEM limits but still in daily service.

Depending on the plan, TruckProtect coverage can support alternators, starters, major sensors, control modules, and even certain wiring harness failures. The goal is not to cover every blown fuse, but to absorb the bigger hits that come from serious electrical breakdowns.

No hype, just practical protection. For many fleets, it is easier to budget for a known monthly or annual coverage cost than to absorb a random 3,000 dollar module failure or a 5,000 dollar harness job on a truck that still needs to be on the road tomorrow.

Conclusion, Commercial Truck Electrical Failures Are High, But They Can Be Managed

Commercial work trucks carry heavier electrical loads, harder duty cycles, more equipment, tougher environments, shorter routes, and more idle hours than most highway tractors. That is why their electrical systems fail more often and earlier in life.

Owners and fleets cannot change the nature of the work, but they can change how they prepare for it. Reducing strain where possible, maintaining connectors and grounds, being smart about aftermarket equipment, and investing in proper diagnostics all help. So does stabilizing risk with coverage that recognizes how often electrical issues strike in this segment.

TruckClub delivers the clarity and technical insight. TruckProtect provides the financial safety net when, not if, electrical systems act up on hard working Class 3 to 7 trucks.